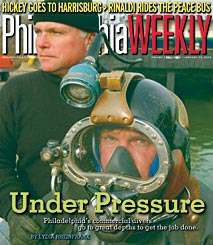

Some Like It Wet

Some Like It Wet

Some Like It Wet

Some Like It Wet

Sixty-three miles southwest of Philadelphia, deep within the Conowingo Hydroelectric Plant, a set of water-flow louvers jams open in the middle of the night, and for a few minutes, the plant's 750-ton hydroelectric generator spins wild in the Susquehanna River, while untapped wattage meant for Philadelphia, Baltimore and Wilmington hemorrhages downstream. The Conowingo night crew quickly shuts down the unit, but in order to get it up and running again, its outer gates must come down and the unit must be drained dry. For that to happen, someone must descend a hundred feet into the dam's watery bowels to clear river trash, muck, whole trees--all the crap that's blocking the gates that seal off the unit.

At 3 a.m., Don Dryden's pager beeps him awake in his New Jersey home. The 49-year-old three-decade veteran of commercial diving knows he and his crew at Dryden Diving Co. Inc. will make the plunge to fix the Conowingo.

Dryden and his crew--Lou Ericsson, Jeff Warner and Ray Santiago--make up one of the most respected commercial diving outfits on the eastern seaboard. Together, they have 70-plus years of experience penetrating and surviving some of the most lethal environments on the planet.

Commercial divers wiggle through raw sewage pipes to fix cracks beneath cities (mostly in the middle of the night when there are fewer flushes). They're called in when ocean tankers run aground, to salvage oil containers, to work with tugs and collapsed piers.

They're involved in building the bridges and offshore oil rigs, the erosion control devices and fish hatcheries. They sweep ship hulls for cocaine, heroin and refugees. They chain saw out dead whales tangled in freighter propellers, and they maintain the nation's major utilities and civic structures. They operate 5, 40, 100, 200 feet down, often without direct exit, their only source of oxygen a vulnerable umbilical air line snaked up to surface.

It's the morning after the Conowingo's breakdown at Don Dryden's shop, an old Victorian house tucked into the tiny town of Swedesboro, N.J. Barrel-solid in thick canvas workman's overalls, a small black hat squeezed down over a face as bright and round as a harvest moon, Dryden looks disapprovingly at his visitor's cheap mesh running shoes. "You can't wear shoes like that," he says directly.

But there's no time to change now. Dryden jumps into a beaten red pickup, stalls at an intersection, turns the engine over again and careens south on Highway 95 toward the Susquehanna River. Dryden devours breakfast on the way: two McDonald's cheeseburgers and a large Coke.

"We get the jobs that are, you know, 'Who the hell are we going to get to do this?'" he says. "Jobs that aren't in anybody's ballpark, and they drop it in ours."

Dryden dives nuclear plants. To be specific, Dryden and his team dive water that surrounds nuclear reactors. They tuck radiation detectors and cold packs against their armpits, knee backs and crotches, and they meticulously preplan the paths of their swim so that once in, they know where not to let a leg dangle or a fingertip swing, how to perfectly twist their bodies to make the fix.

Dryden dives nuclear plants. To be specific, Dryden and his team dive water that surrounds nuclear reactors. They tuck radiation detectors and cold packs against their armpits, knee backs and crotches, and they meticulously preplan the paths of their swim so that once in, they know where not to let a leg dangle or a fingertip swing, how to perfectly twist their bodies to make the fix.

Most of the time Dryden and his team work blind.

"Opening your eyes gets distracting," says Dryden. "Visibility is usually so bad, it's easier to feel with your hands."

It's not dangerous work, Dryden says of commercial diving in general, "but it has the potential of being dangerous."

That's what they all say.

No one knows exactly how many fatalities and injuries occur each year in commercial diving. The Department of Labor, which keeps the country's most extensive database of job-related fatalities and injuries, lumps commercial diving incidents in with accidents at offices and flower shops.

A maritime enforcement officer for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) says commercial diving accidents often get filed under motley construction categories, routinely slipping through statistical cracks.

"Your average businessman standing up top has no idea what's going on down there in the water," says Ross Saxon, executive director of the Association of Diving Contractors, an industry trade organization. "Commercial diving is very misunderstood, and for that reason, often unreported."

Some 4,000 commercial divers belong to the Association of Diving Contractors International in the United States, and even the best-trained face intense risks. In addition to decompression sickness (the bends), gas toxicity and all the bloody threats of physical injury that go along with operating heavy machinery, a diver must contend with the deadliest foe: differential pressure or Delta P, which is any situation where there's a pull or push in the water due to a variance in water levels.

Case after case in OSHA's database reads: "divers drawn into water pipes and drown," "diver drowns while inspecting tubes at dam," diver "trapped in sluice gate." An elbow gets stuck, an air hose, a hand. Diver drowns.

Several years ago a diver working along the inside wall of the Pedro San Miguel locks in the Panama Canal was fixing a valve whose function was to allow excess water inside the lock to escape and fall some hundred feet down to the lock's outer side. The diver was sucked up against the valve's 4-inch opening, the pull so fierce on his body that in a matter of minutes his intestines were sucked out. He was eventually pulled, alive, from the water, but died later from hypothermia.

Several years ago a diver working along the inside wall of the Pedro San Miguel locks in the Panama Canal was fixing a valve whose function was to allow excess water inside the lock to escape and fall some hundred feet down to the lock's outer side. The diver was sucked up against the valve's 4-inch opening, the pull so fierce on his body that in a matter of minutes his intestines were sucked out. He was eventually pulled, alive, from the water, but died later from hypothermia.

When Dryden Diving inspects and repairs the up-river face of the Conowingo Dam, looking for fissures and damage to the repair gates caused by the Susquehanna River's massive force and debris, they deal with Delta P on a freaky scale. They swim the walls slowly, looking for places where the river has busted through.

"You can hear the cracks when you're under there," Dryden says. "It actually sounds like a freight train. But you don't know exactly where it is. So you start inching down the face while you hold a burlap bag way out in front of you as you go, very slowly, bit by bit. You know you've found the gap when fffffffftpppttptp, the bag just disappears from your hand."

The commercial diver's world is a lonely place. "You go 200 feet down, you're no longer capable of living on the surface," says Dryden, explaining that under that kind of pressure, the human body couldn't survive on dry land. "You go 1,000 feet up a pipeline, there's no one who's going to be able to help you but that guy tending hose. And he's only useful to a certain point. You're no better off than if you were on the moon."

Dryden has taken a lot of wear and tear over the years. Both wrists were injured when he tried to protect himself from a crew boat that was crashing down on top of him. A 60-foot dock piling fell on him when he was 23, rupturing his kidney and folding his foot in half, lengthwise, so that his pinkie toe touched his big toe, and his foot started to rot. Recently, he slipped on a concrete form covered in oil and dew. He's getting a new hip this winter. But Dryden shrugs off his injuries. They're just part of the life, part of the job.

"I feel great when I'm in the water," he says.

As Dryden rounds the final curve of road, a sheer wall of turbulent white water and concrete looms ahead like the mouth of a mythical whale: the Conowingo Dam.

It took 4,000 men two years to complete the Conowingo. Spanning 4,648 feet, a hundred feet high, with 38 million gallons of Susquehanna River raging through each minute, the structure was a national wonder when it opened in 1928. Now run by Exelon Power, the hydroelectric plant continues to pump power all over the mid-Atlantic region.

It took 4,000 men two years to complete the Conowingo. Spanning 4,648 feet, a hundred feet high, with 38 million gallons of Susquehanna River raging through each minute, the structure was a national wonder when it opened in 1928. Now run by Exelon Power, the hydroelectric plant continues to pump power all over the mid-Atlantic region.

Dryden parks in a ditch at the dam's far side.

Sometimes divers are in the water all day and all night. Other times, when depths are great, they make precision dives, staying at the bottom only briefly to do their work. This is one of the latter jobs. Much of the divers' time is spent waiting. On this job, they'll end up spending 13 hours on the dam in a single day.

Inside the plant, dripping tunnels roar with turbine power and a control room blinks with 1920s gauges linked to modern computers. High voltage warnings line the staircases. The Conowingo renders a human small. Pressure and power burrow into your marrow.

Wandering, safe within walls, deeper into the dam's creepy interior, one can't help but question the Dryden divers' sanity.

Do they do it for the money?

A novice, or "tender," fresh out of training school, which costs around $9,000 for five months, will make, on average, only $9 to $10 an hour offshore (on oil rigs) and $12 an hour inland. Seventy percent of tenders bail withintheir first year, and only one in 20 of the remaining makes it past the five-year mark. Divers 40 years or older are rare.

"Slackers just don't cut it," says Tamara Brown, owner and executive director of Divers Academy International, a commercial diving school in Camden. "You have to be aggressive but very patient and, most importantly, willing to be part of a team."

Teamwork is what makes Dryden Diving stand out among other companies.

"Somebody makes a mistake, then you're all in trouble," says diver Santiago. "But this group? We talk and we plan what we have to do so that everybody's on the same page. A lot of companies don't do that."

Dryden pays his most experienced divers, who are unionized, $50 to $60 an hour. That's about $10 more than typical union pay. Nonunion divers get even less, and are generally suspect. Union divers abide by new regulations--they are "recommended," though not federally enforced--including requirements on crew size and equipment.

Dryden's picky about who he hires, and he believes in treating his employees well. "You're depending on each other for your lives," he explains. "If you're not paying well, it'll come back to haunt you."

These guys are on call 365 days a year, 24 hours a day, regardless of the weather. Maintaining a healthy family life is a challenge. Vacation is rare.

Someone finally sticks his head into the break room. "They're ready for you."

Hard hats, eyewear, hoods, gloves, everything on.

It's 6:30 p.m. on top of the Conowingo Dam. A wind rips lip-crack cold down the Susquehanna River, slamming a turbulent black sea of logs and trash against the dam's upstream wall. Cars slash by. It's been raining all day, spitting ice-cold. The Conowingo crew, five men in heavy brown worksuits, ring a 30-by-5-foot open compartment halfway across the dam's upper deck, mere feet from the crossover road. Cigarettes wag.

The men grip safety ropes lashed to a massive steel gate dangling from a 40-foot crane far above the hole. Shock-white work lights beam down on all, and the river below glints black.

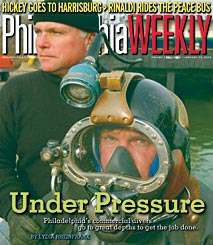

Into the light steps Ericsson, neck to toe in black rubber. He's a neoprene king, a grand actor ready for his curtain call, a surgeon prepping for an operation. With his arrival, the other Dryden divers begin their well-honed dance.

Dryden holds up a 20-pound weight belt. Ericsson shrugs it on. Warner fastens 5-pound flexi-weights around Ericsson's ankles. Ray checks hoses and coils cable nearby.

Dryden lifts the helmet, a 30-pound sphere, and helps Ericsson put it on, fastening it with a helmet dam. Suarez holds up gloves, and Ericsson pushes in his hands. They work seamlessly and without words. The rain blows sideways. Then, like a giant insect cleaning its antennae, Ericsson runs his hand the length of his light, which arcs from the back of his head to the front, and heads for the orange ladder leading down to dam's black hole.

Dryden takes his spot at the communications box, an open plastic suitcase from which rasps the in and out and in of Ericsson's breathing. He holds a stopwatch and a laminated table of depths and permissible diving times. The dive will be clocked to the second to ensure Ericsson's safety.

Warner mans the air compressor that chugs nearby, monitoring Ericsson's depth and air pressure. Just outside the light squats a decompression chamber, a large white tube into which divers can crawl (or be thrown, unconscious) when they're experiencing the bends or other gas/blood emergencies.

Warner mans the air compressor that chugs nearby, monitoring Ericsson's depth and air pressure. Just outside the light squats a decompression chamber, a large white tube into which divers can crawl (or be thrown, unconscious) when they're experiencing the bends or other gas/blood emergencies.

Suarez tends hose at the hole edge, gripping the five-cable bundle bound tightly with duct tape: air hose, light cable, backup air, safety line and communications line. One tug from the diver means he's okay, two means give slack, three take up slack, four means bring him up. Four four four means emergency! Get him out get him out!

"And five means, tie me off, I'm going for a beer," says Dryden.

''At surface," says Ericsson. Dryden clicks the stopwatch to go. The Conowingo crew surrounds the hole, manning a large gate that will eventually be lowered into the hole, once Ericsson has cleared the debris below.

Ericsson's shoulders disappear into the murk, followed by his head. His light, which is attached to his helmet, glows eerie greenish-yellow just beneath the surface. Then it, too, is gone. All of Ericsson is gone but his smooth, regular breathing, which roars in and out through the communications box. The watch hand spins.

"Slack up," rattles Ericsson's voice, rising in pitch as the deepening water presses against his throat.

"Slack up!" calls Dryden.

Suarez pulls up slack. Warner coils cable.

Minutes pass as Ericsson goes down. The tension of concentration is palpable among the Dryden dive crew.

Suarez slowly feeds out hose. Cars pass. The air compressor sputters on.

"Bottom," rasps Ericsson. He's 91 feet down. Dryden explains that Ericsson's now clearing debris, making way for the gates to drop and seal.

A few minutes later, from Ericsson: "Let the gate down."

"Gate down, slow!" says Dryden.

The Conowingo men signal up to the crane operator, and the machine above roars to life as it lowers the gate into the water, down over Ericsson's head, a grinding so loud it grates the spine, even up on top.

"Come on guys," Dryden chides the gate crew. "We're burning up bottom time."

"Come on guys," Dryden chides the gate crew. "We're burning up bottom time."

"Stop," says Ericsson from far below.

"Stop!" says Dryden.

"Checking under the gate now," says Ericsson. In blackness, he's shoving and pulling more trees and metal and bracken from under the gate and pushing it through the compartment's other side. His breathing deepens but remains steady.

"Lower the gate."

"Lower the gate!"

The gate is lowered a little more, grinding, roaring, clanking. What would happen if the gate fell, trapping Ericsson's arms under an inches-wide gap between gate bottom and dam floor?

A cracked and warped bucket bobs strangely to surface, turning on its side like a dead fish.

"The gate's down," says Ericsson.

"Coming up."

And up he comes, as slowly as he descended. Slower even. The crew stares into the black, waiting, until finally the glow appears and Ericsson's head breaks the surface.

He emerges like a 6-foot shining cockroach.

Cars on the dam road slow to gawk at this strange creature.

It took Ericsson 12 minutes, bottom time. He waits a moment as his teammates move and re-lash the orange ladder into another dam compartment, and down again he goes, this time for 11 minutes.

And so goes this dive, without a single snag.

"I've been working here 35 years," says Steve Delp, who plans maintenance for the Conowingo, "and Dryden Diving is the best crew we've had. They're out there working in the cold, and I'm in here inside my office in the dam, looking out my window. They come out purple sometimes. I can't see anything that's going on down there, but I can trust that they've got it right every time."

At night's end, Dryden nods to Ericsson, "Good dive."

"It's not that these guys are brave," says Dryden later. "It's just that it doesn't bother them. If you were scared to the point you were peeing in your pants, but you went in and did it anyway, then you're brave. But for these guys, it's just what they do."

Lydia Rheinfrank is a freelance writer from Philadelphia.